Ticks

Ticks are small blood-feeding parasites that affect various mammals, including horses, humans, dogs, and cats, and their numbers are increasing in the UK.

They are classified within the Acarina group, which also includes spiders, mites, and scorpions. These parasites exhibit a range of colors from reddish to dark brown or black and vary in size based on their species, age, sex, and feeding status.

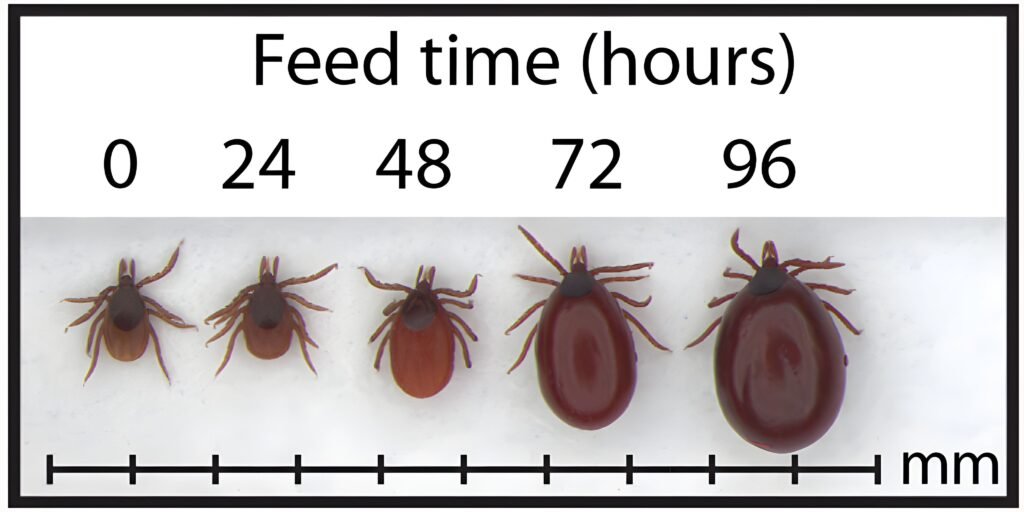

Unfed ticks can measure as little as 0.5mm (similar to a poppy seed) to 3mm (about the size of a sesame seed), appearing small, oval, and flat.

After feeding, their bodies swell significantly, resembling a grain of rice or a small bean.

Ticks lack wings and the ability to jump; instead, they move by walking on the ground and climbing plants, where they attach to passing or resting hosts using specialized hooks on their legs.

In Britain, there are over 20 tick species, many of which are known to latch onto humans or pets. The most common species vary by region, habitat, and local wildlife, with three predominant types: Ixodes ricinus (commonly known as the sheep tick, wood tick, deer tick, or castor bean tick), Ixodes hexagonus (the hedgehog tick), and Dermacentor reticulatus (the marsh tick).

Wildlife and farm animals are the primary hosts for ticks, but since horses, humans, and pets emit similar signals such as body heat and chemical cues, ticks will instinctively climb onto them from the tips of grasses or the leaves of shrubs and bushes.

TICK BEHAVIOR

Once a tick has climbed onto a host, it will crawl around to find an optimal spot to bite before attaching and feeding, a process that can last up to three days.

After feeding, they will drop back to the ground to molt or lay eggs. Consequently, the highest concentrations of ticks are typically found in areas frequented by livestock, such as water sources, feeding areas, and favored resting spots (e.g., beneath large trees in pastures). In these locations, a horse may acquire multiple ticks.

TIMING AND LOCATIONS OF RISK

Ticks are more commonly found in regions with high densities of livestock and wildlife, particularly in rural areas.

RISK TIMES & AREAS

Ticks are commonly found in regions with high populations of livestock and wildlife, particularly in rural settings such as forests, woodlands, and grasslands like heath and moorland.

Certain locations in the UK are often identified as tick ‘hot spots,’ including the New Forest, Exmoor, the South Downs, Thetford Forest, the Lake District, the North Yorkshire Moors, and the Highlands and Islands of Scotland.

Additionally, localised ‘hot spots’ can emerge in various other areas. While the risk of tick bites is generally higher from April to November, ticks can remain active at temperatures as low as 3.5°C.

They seek refuge in plant debris during colder months, and as winters become milder, the likelihood of increased tick populations and incidents rises.

EFFECTS

Experiencing one or two tick bites is usually not harmful to an animal; issues typically arise only when infestations become significant, leading to irritation and potential anemia due to blood loss.

In rare cases, a host may suffer from general toxaemia and immune challenges resulting from exposure to substantial amounts of tick saliva. More concerning is the fact that many ixodid ticks can transmit various harmful microbial diseases, including Lyme Disease (Borreliosis), Babesiosis, Anaplasmosis/Ehrlichiosis, Bartonellosis, Q-fever, and the Louping ill virus.

LYME DISEASE

Lyme Disease is a serious tick-borne infection caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which can affect both animals and humans.

Clinical symptoms manifest in fewer than 10% of infected horses, with the most prevalent signs being lameness and changes in behavior. The lameness typically affects larger joints and may shift from one limb to another. Horses may exhibit generalised stiffness, sometimes accompanied by fever.

Laminitis has been occasionally linked to Lyme disease. Identifying behavioral changes can be challenging. In addition to a reluctance to work—potentially due to musculoskeletal pain—owners often report increased irritability and altered attitudes in these horses.

The diagnosis of Lyme disease in horses presents significant challenges for two main reasons: first, horses frequently experience various musculoskeletal injuries and conditions that can lead to lameness, which may not necessarily be linked to Lyme disease; second, the blood tests typically employed for diagnosis identify antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi. Given that subclinical exposure is prevalent, a positive antibody test merely indicates that the horse has encountered Borrelia burgdorferi, rather than confirming that its illness is attributable to Lyme disease.

TICK REMOVAL

While not all ticks transmit disease, it is advisable to promptly remove any attached ticks. The longer a tick remains attached, the greater the likelihood of pathogens entering the host’s bloodstream. Regular inspections can help detect ticks before they have the opportunity to attach and feed.

For safe tick removal, consider using the Tick Twister, available in our online shop for just £3.50.