Seasonal Parasite Management

Our horses benefit from carefully scheduled worming programs; we regularly clean our paddocks, quarantine new arrivals, and rotate grazing areas. However, one of the most significant factors affecting parasite levels is beyond our control: the weather. Variations in temperature and rainfall greatly influence the presence of worms in our horses.

The National Animal Disease Information Service produces a monthly Parasite Forecast for farmers, utilising comprehensive data from the Met Office.

This forecast monitors weather changes to identify potential threats to sheep and cattle.

Typically, milder and wetter conditions are more favorable for parasites; warm temperatures promote feeding and breeding activities, while dampness ensures their continued movement and activity.

Spring and autumn are naturally peak seasons for parasite proliferation. To effectively combat this, we ideally require weather extremes—harsh, cold winters and hot, dry summers—to disrupt the lifecycle of parasites.

RAINFALL AND MOISTURE LEVELS

Under ideal conditions, the redworm, which is the most prevalent horse parasite, can progress from an egg deposited in a dung pile to its infective larval stage in as little as five days.

During this period, the minuscule larvae, nearly invisible to the naked eye, can travel approximately one meter. This distance is quite remarkable, but with rainfall, their potential range can extend to as much as three meters in wet conditions.

This mobility is crucial for their survival; horses typically avoid grazing near faeces, so the farther a larva can move towards an appealing blade of grass, the higher its chances of being consumed by a host, thus continuing its life cycle.

Conversely, hot and dry conditions, which are rare in the UK, can be detrimental. A lack of moisture can slow or completely halt the development of the larvae and dry out dung piles, exposing the eggs to harmful UV rays.

In such dry conditions, harrowing can be an effective method of parasite control. However, in the presence of moisture, it merely redistributes worm eggs across the pasture, allowing larvae to infiltrate the protective layer of vegetation.

TEMPERATURE

Worm eggs are typically quite resilient, with roundworm eggs being particularly robust.

The thick, adhesive shell of the ascarid enables it to withstand extreme temperatures in the UK for as long as 10 years.

Additionally, some redworm eggs can survive the winter, enduring severe frosts and hatching in the spring when temperatures rise.

AN ORABATID MITE

Frost can effectively eliminate tapeworm eggs; however, a single harsh winter is not sufficient to completely eradicate them.

Tapeworms rely on intermediate hosts—small orabatid mites that are well-adapted to survive the British winter.

Consequently, there will be a significant number of these infected grassland mites available to sustain the tapeworm population through the colder months.

Temperature also plays a crucial role in the behavior of the worms. The activity of redworms significantly decreases when temperatures drop below 6 °C, and the transition from egg to infective larval stage can take several weeks in winter conditions.

Nevertheless, some worms manage to endure the winter cold until they are consumed by a horse, where the warm internal environment triggers their activity and continues their lifecycle.

PROTECTING OUR HERD

Under typical UK weather conditions, a healthy adult horse can adhere to a straightforward plan involving testing and treatment: conducting worm egg counts in Spring, Summer, and Autumn, testing for tapeworms every six months, and administering a proactive winter treatment to address the potential presence of encysted redworms.

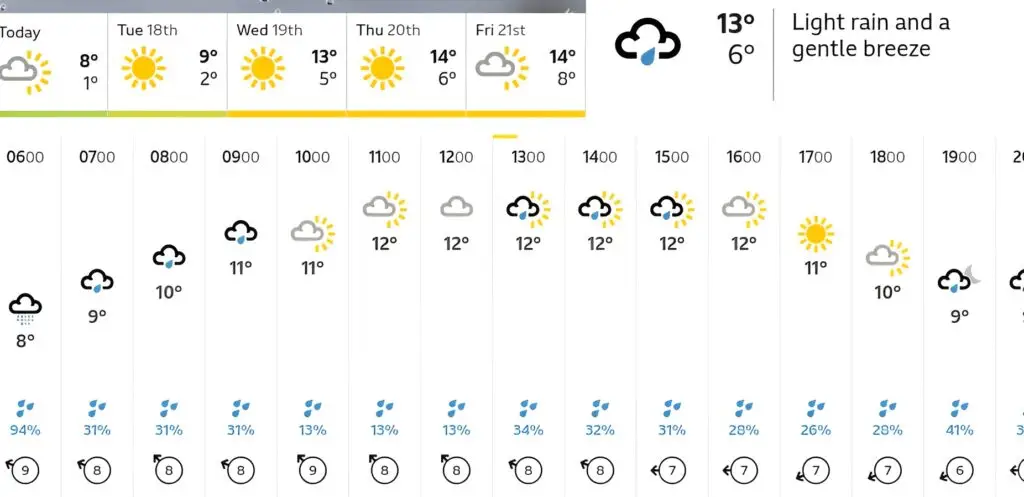

However, an unusually mild winter combined with a wet summer can significantly heighten the risk of harmful parasite infestations.

During these prolonged warm and damp conditions, it is essential to closely monitor our horses and consider shortening the interval between worm counts to every eight weeks, especially for young, elderly, or vulnerable horses.

Additionally, we should aim to disrupt the lifecycle of the worms through effective pasture management and be prepared to apply the appropriate chemical treatments at the right time to prevent parasite levels from reaching a point that could jeopardise the health of our horses.