Redworm

Lo

There are two types of redworm that affect horses: large and small strongyles.

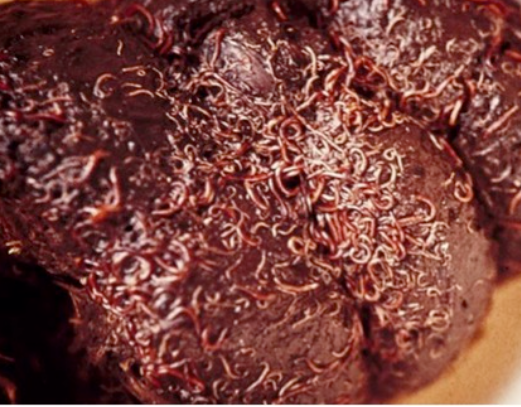

SMALL REDWORM OR CYATHOSTOMINS

Small redworms represent the most prevalent and potentially hazardous parasitic threat to equine health. They possess a rapid lifecycle, completing it in as little as five to six weeks, and can reproduce in significant quantities; approximately 95% of the parasitic load in horses consists of small redworms. In addition to the challenges posed by large populations of adult redworms, cyathostomes exhibit a unique developmental phase where the larvae of certain species penetrate the horse’s intestinal wall and encyst, which can lead to severe complications upon their re-emergence. Small redworms can grow up to 2.5 cm in length, are slender, and typically exhibit a reddish hue (while unfed specimens appear white).

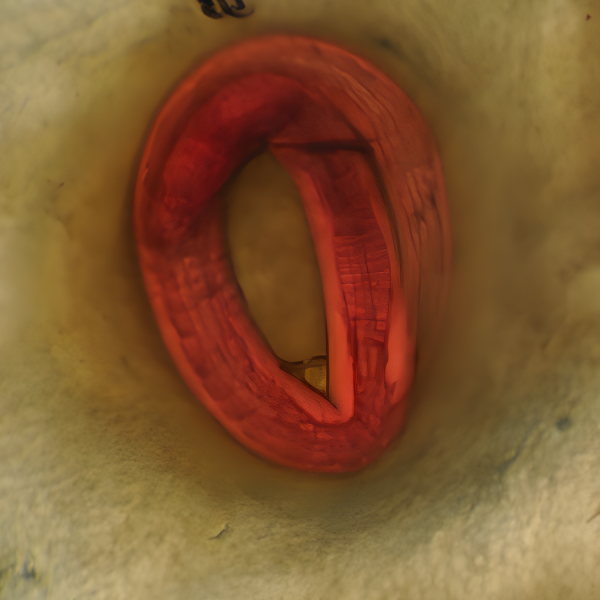

LARGE REDWORM OR STRONGYLUS VULGARIS

Although large redworms have the potential to inflict greater harm on horses, their prevalence has significantly decreased over the past four decades due to effective deworming practices. These worms have a migratory larval stage that can obstruct blood vessels, resulting in damage to essential organs and potentially causing life-threatening hemorrhages and internal bleeding. Large redworms are darker red and larger than their small counterparts, reaching lengths of up to 5 cm.

SYMPTOMS

Infections caused by both large and small redworms can manifest through various symptoms, including weight loss, poor condition, anemia, a distended abdomen, a dull or unkempt coat, as well as diarrhea and colic. Over time, a small redworm infestation can severely compromise the intestinal wall, impairing the horse’s ability to absorb nutrients effectively. This may lead to the horse becoming a chronic ‘poor doer,’ and in severe cases, a significant infestation can be fatal. It is also important to note that a horse may appear completely healthy while still harboring a considerable worm burden.

Encysted Small Redworm

Many species of small redworms undergo a distinct lifecycle phase that poses significant health risks to horses. The L3 larval stages penetrate the gut wall of the large intestine and become encysted. Some of these larvae continue their development within the gut wall, later emerging as adult worms that lay eggs in the large intestine. Conversely, other larvae may remain encapsulated for extended periods, ranging from months to years, in a dormant state referred to as inhibited encysted larvae. Large numbers of these encysted larvae can accumulate along the intestinal lining, hindering nutrient absorption and potentially leading to weight loss and severe health complications. They remain in this state until environmental changes, such as the transition from winter to spring, prompt a ‘mass emergence’ from the gut wall. This sudden activity can result in life-threatening bowel inflammation, known as colitis (larval cyathostominosis), in horses.

WORM COUNT TESTING

Worm egg counts serve as an effective method for identifying the adult egg-laying phases of both small and large redworms, as well as roundworms.

It is recommended to conduct these tests every three months throughout the year to monitor infection levels and initiate treatment if the count exceeds 250 eggs per gram.

While a worm egg count does not differentiate between large and small redworm eggs, this is not a significant issue since the treatment remains the same for both types of parasites.

It is important to note that horses are not expected to be entirely free of worms; administering medications in this manner helps mitigate resistance and is beneficial for both the horse and the environment.

It is important to recognise that a worm egg count will not reveal encysted stages of small redworm, as larvae do not produce eggs.

There is now a blood test that is an antibody test aimed at detecting infection levels by assessing the horse’s immune response that can be performed by your veterinarian. If the test is positive the animal will require evidence-based treatment, it is advisable to administer an appropriate wormer annually during the winter months to protect against potential encysted redworm.

Conducting regular worm egg counts allows for effective monitoring of a horse’s worm burden and contributes to a broader understanding of their overall health. Within a single herd, it is common for 80% of the worms to be found in just 20% of the horses. This phenomenon occurs because certain animals are more susceptible to carrying parasites, which may be due to age, a weakened immune system, or favorable gut conditions and grazing habits. These animals, referred to as “high egg shedders,” should be identified within herds for better management. Explore worm egg count options here.

SMALL REDWORM ANTIBODY TEST

Researchers have created an antibody test designed to detect infection levels by evaluating the horse’s immune response. Experts advise that horses with previous fecal egg count results exceeding 250 eggs per gram within the last year are classified as high risk and may not be suitable candidates for this advanced test, thus requiring a routine treatment.

TREATMENT

Several anthelmintics are approved for the treatment of adult redworm, including fenbendazole, pyrantel, ivermectin, and moxidectin.

Among these, only moxidectin and a five-day course of fenbendazole have proven effective against the encysted forms of small redworm.

Recent evidence indicates that cyathostome populations have developed resistance to the older anthelmintics, fenbendazole and pyrantel.

Therefore, these medications should only be administered following a resistance test to ensure their effectiveness.

For further information, please inquire. Additionally, the egg reappearance intervals for other anthelmintics are decreasing, which serves as an early indicator of potential resistance development. It is crucial to implement targeted parasite control strategies to mitigate the emergence of resistance and extend the lifespan of these treatments.

Consequently, moxidectin should be reserved for winter administration, while other anthelmintics can be utilized as needed throughout the rest of the year. In cases where resistance is not present, these medications remain effective, with pyrantel and fenbendazole being the preferred options for treating roundworm or pinworm infections.