Bots

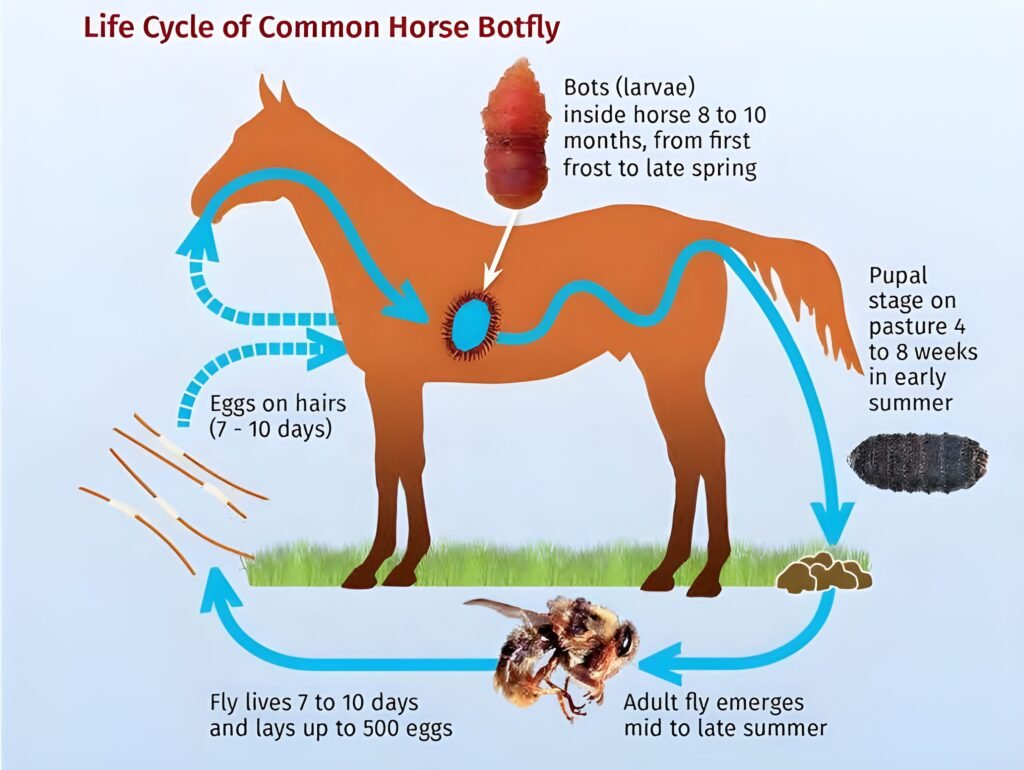

Bots (Gasterophilus spp.) are not classified as horse worms; instead, they are flying insects resembling slender wasps, with a life cycle closely associated with horses. Their development consists of four distinct stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult fly, with only the adult stage existing independently of their equine host.

EGG STAGE In the UK, three primary species that impact horses can be identified based on their egg-laying locations on the animal: G. intestinalis, commonly known as the common bot, deposits pale yellow eggs on the horse’s body hair, particularly on the shoulders and forelegs.

As the horse rubs against surfaces, these eggs are ingested into its mouth. The warmth and moisture in the mouth stimulate the eggs to hatch into pinhead-sized larvae within approximately a week, which then burrow into the gums or beneath the tongue. Less frequently encountered is G. nasalis, known as the throat bot, which lays yellow eggs in the chin and throat area beneath the horse’s jaw.

Additionally, G. haemorrhoidalis, or the nose bot, places black eggs on the hair surrounding the horse’s lips. The larvae from these eggs also hatch and migrate into the mouth within a few days, subsequently burrowing into the gums and beneath the tongue.

LARVAL STAGE

In all species of bots, these small, mobile larvae reside in the mouth for a duration of three to four weeks before gradually migrating down to the gastrointestinal tract, where they burrow into the gut wall.

The common bot attaches itself to the upper section of the stomach, the throat bot locates itself in the small intestine near the duodenum, and the nose bot adheres to the mucous membranes of either the stomach or rectum.

Once established, the larvae remain in this location for approximately 10 to 12 months, consuming the horse’s gut contents and developing until spring or early summer, at which point they detach from the gut lining to be excreted in the host’s feces.

It is understandable to be startled by the appearance of the pupae of G. haemorrhoidalis (the nose bot), which can be seen attached to the mucous membrane of the horse’s rectum, protruding through the anus as they grow and mature.

This sight is certainly unexpected in such a sensitive area.

They are exclusively found in pasture environments, as they do not thrive well on bedding in stables.

The pupae exhibit sensitivity to frost and moisture, making the surrounding environmental conditions crucial for the parasite’s success.

PUPAL STAGE

The bot larvae undergo pupation in the soil for a duration of 3 to 5 weeks, after which the adult bot fly emerges.

ADULT FLY

Adult bot flies are medium to large insects with brown stripes, measuring between 10 to 20 mm in length. They resemble a slender wasp or drone bee and possess a single pair of wings. After hatching, the adult flies live long enough to mate and deposit their eggs on horses, typically dying within about two weeks once they have depleted the nutrients from their larval stage.

EFFECTS

In rare or extreme instances, bots may lead to disease or discomfort in horses, and it is possible for a significant number of them to exist without any visible clinical signs.

The initial larval stages migrating within the mouth can result in inflammation of the oral cavity and gums, and in exceptional cases, may lead to the formation of purulent discharges in the sinus tracts.

Once the larvae reach the intestinal tract, a severe infection can hinder a horse’s ability to properly digest food, leading to a deterioration in overall condition. Bots may induce mild gastritis by damaging the stomach lining, with their burrowing activity causing ulcerations and abscesses that can provoke colic.

The presence of digestive juices can exacerbate these ulcerations, potentially resulting in breaches of the stomach lining, which can be fatal due to peritonitis. Fortunately, such severe outcomes are exceedingly rare.

DETECTION

Identifying bot infections can be challenging. There is no reliable method to test for the presence of larvae within the horse, and it is uncommon to observe larvae being expelled in feces.

If bot eggs are detected on one horse within a herd, it is advisable to assume that all horses require a deworming treatment for these parasites.

MANAGEMENT & TREATMENT

While the term “worming” is commonly used to describe the treatment of these parasites, it is important to note that they are not true worms like redworm or roundworm, but rather flies.

Treatment effectiveness is contingent upon the specific life stage of the bots.

FLIES:

Insect repellents may be employed to deter bot flies, although they may not provide complete protection.

EGGS:

Once eggs are deposited on the horse’s coat, they can be removed using a bot knife or a blunt metal edge to reduce the risk of infection.

LARVAE:

Ingested larvae cannot be treated until they reach the horse’s stomach. Veterinary recommendations suggest targeting them with a single treatment after the first frost of winter, which will eliminate bot flies and prevent further reinfection.

Ivermectin and moxidectin are both effective options, and it may be beneficial to combine this treatment with the winter deworming regimen for encysted redworm.

PUPAE:

These are sensitive to frost and moisture.

GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION

Bot species are geographically distributed.