Which Wormer Should I Use?

Prior to the introduction of the first deworming treatments, numerous horses experienced severe and occasionally fatal illnesses due to parasitic infections.

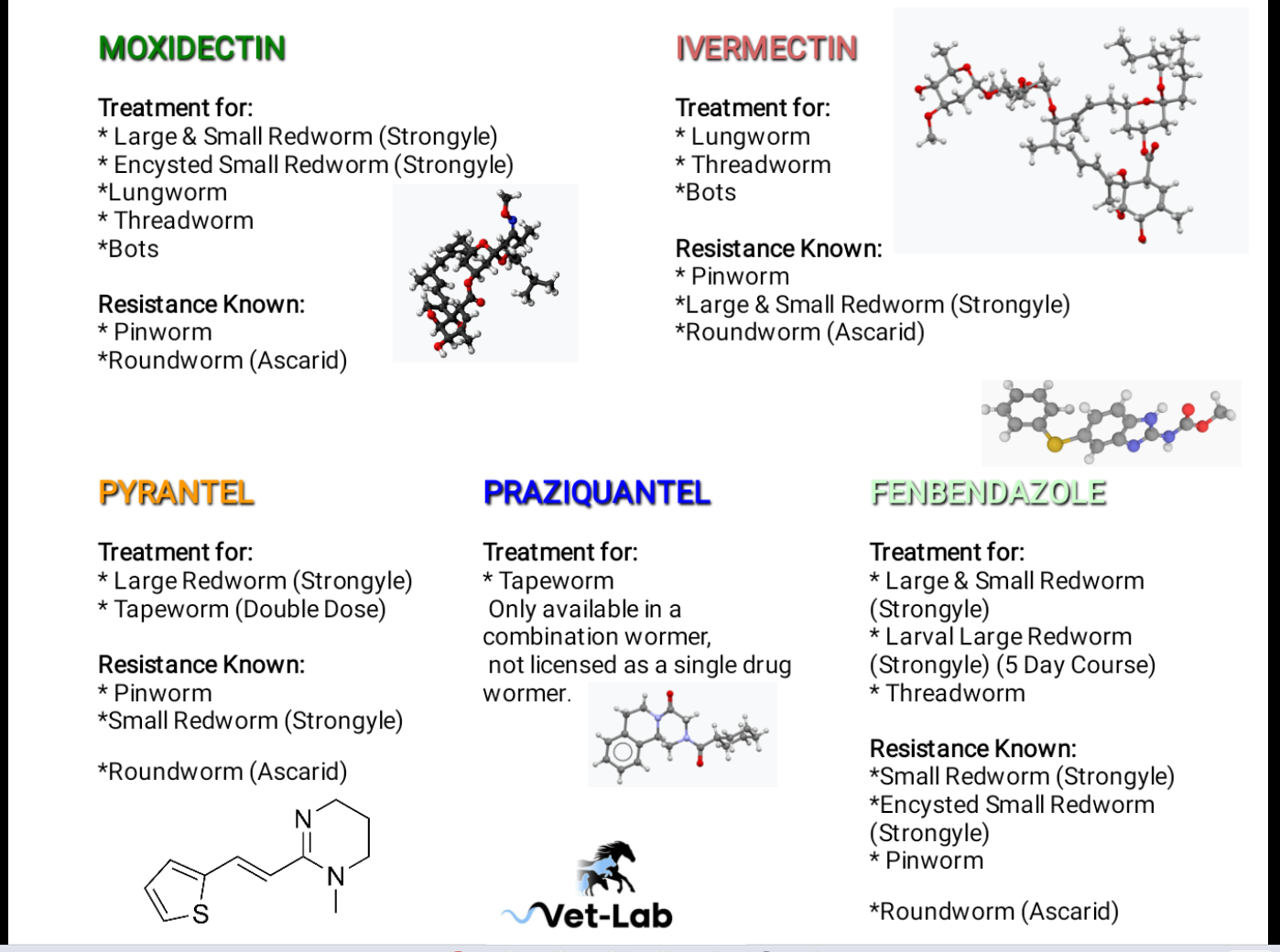

In the 1960s, the market saw the launch of the initial horse deworming medications, starting with fenbendazole (branded as Panacur), followed by pyrantel, which was initially known as Strongid P.

This development provided us with affordable and efficient solutions to prevent worm-related harm in horses. Regular administration of these treatments significantly improved equine health.

The subsequent approval of ivermectin, moxidectin, and praziquantel throughout the 1980s and 1990s briefly equipped the equine industry with a comprehensive and effective arsenal to combat parasites.

60 years later, the situation has changed significantly.

Continuous exposure to these five chemicals has enabled worms to develop increased resistance to the medications.

As a result, they are no longer affected by the treatments, making it ineffective to administer a wormer with the expectation of success.

Currently, no new wormers have been approved for use in horses, and none are anticipated in the near future due to the high costs associated with licensing and the lower priority given to equine health.

The table below outlines the resistance status of these five primary wormers.

It is essential to exercise great caution in managing parasite loads.

– Instead of attempting to eliminate all worms, which is unfeasible, our goal should be to control them at levels that do not harm the horse.

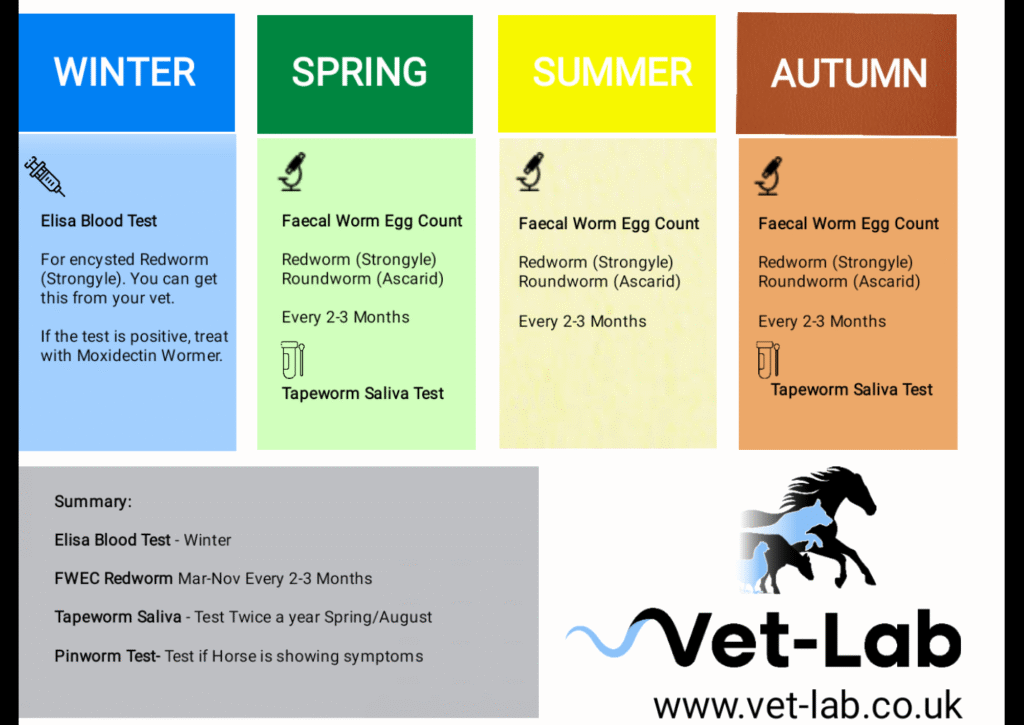

– This involves conducting tests prior to treatment to apply dewormers only where necessary, thereby minimising exposure and delaying the onset of chemical resistance.

– When treatment is required, it is important to select the appropriate medication by understanding which parasites the chosen dewormer is effective against and considering the seasonal timing.

– Additionally, performing reduction tests is crucial to confirm the effectiveness of the treatment.