Wormer Resistance

The concept of ‘wormer resistance’ is likely familiar to many of us; it refers to parasites that have adapted and are no longer susceptible to the selected worming treatments.

Similar to the situation with antibiotics, this development restricts the effective medications available for managing infections.

Currently, there are no new wormers in the pipeline. If we encounter resistance to all existing wormers, we may have to cease keeping horses on that land, which could have serious consequences.

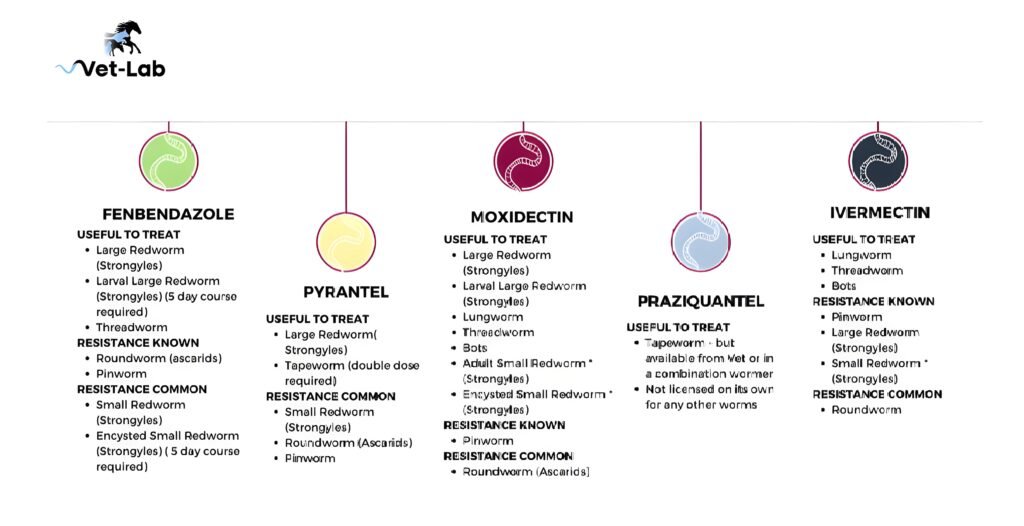

The table below outlines the resistance status of the five primary wormers.

WHAT CAN WE DO TO SLOW RESISTANCE?

Safeguard essential medications Minimise environmental worm challenges

SAFEGUARD ESSENTIAL MEDICATIONS

While it may seem straightforward, a parasite can only develop resistance to a medication when it is exposed to it.

By administering wormers only when necessary

—utilising worm egg counts and other diagnostic methods to limit the frequency of chemical treatments

—we can extend the effectiveness of our worming agents.

Establish a worming strategy that aligns testing and treatment with the appropriate seasons.

Avoid using excessive measures for minor issues.

Whenever feasible, reserve moxidectin (Equest) for a single winter application to address encysted redworm, while employing other effective wormers throughout the year to target adult stages of small redworm and other parasitic threats.

We can implement reduction tests to assess the effectiveness of dewormers and track resistance; conduct a worm egg count prior to treatment and again two weeks post-dosing.

Avoid underdosing

—accurately determine your horse’s weight and administer the appropriate dosage. Exposing worms to insufficient doses of wormers is a guaranteed way to foster a population of resistant worms.

MINIMISE ENVIRONMENTAL WORM CHALLENGES

In simple terms, this involves diligent manure management—regularly picking up droppings!

Equally important are husbandry practices and pasture management techniques that disrupt the worm lifecycle and lessen our dependence on chemical treatments.

Worm larvae excreted in feces hatch and become active within seven days, at which point they can leave the dung piles and reinfect the pasture.

The milder and wetter the conditions, the further and faster the larvae can spread.

Collecting droppings twice a week, even during winter, is a wise investment in your worm control strategy, and ensure that manure heaps are kept away from grazing areas.

By taking these straightforward steps to combat resistance, we can ensure the long-term effectiveness of our wormers, allowing for many enjoyable years of horse ownership.

HOW CAN I TELL IF THE WORMS ARE RESISTANT

Over time, worms can develop resistance to various chemicals they encounter.

It is advisable to conduct resistance testing to confirm the effectiveness of your wormer.

This is particularly crucial when using fenbendazole (Panacur), as there is significant documentation of resistance to this treatment.

To evaluate the parasite load in your horse, a worm count is performed, and a dose may be administered if needed.

Two weeks after administering the wormer, a follow-up fecal sample should be sent for analysis. If the results show a reduction of less than 85% to 95%, it indicates that the worms are resistant to the chemical used.

If resistance is detected, it is important to seek assistance or consult your veterinarian for alternative strategies to address the issue effectively.